Prologue

You might not know it, but Firefox was once widely considered to be an innovative browser. It wasn’t just an alternative to Internet Explorer (and now Chrome). Firefox introduced honest-to-goodness new features that people loved and rely on to this day.

I start there to properly contextualize this post - Firefox wasn’t just different – it was better. Being better was how Firefox gained marketshare from Internet Explorer, and I don’t think it would have been enough to just be different. After all, there were plenty of different browsers back then - just like on iOS today, you were able to get many different Internet Explorer shell browsers – mostly, they were just “different”.

After a while, the advertising company helping to fund Mozilla’s open source largesse decided that they wanted to own the web all for themselves, and so introduced Chrome.

Spurred on by those very same advertising dollars (and campaigns, lest we forget), Chrome dominated the browser space in the years to come.

Chrome did a lot of things differently from its competition, and a lot of it was better. Some of it was just different, though.

Just as the adherents of cargo cults confuse what actions lead to material wealth, imitating behaviors and rituals associated with more advanced societies, end users and tech workers alike are wont to copy more commercially successful products in order to catch a little of the shine that comes to the more successful product. Unfortunately, just as with cargo cults, imitating behaviors doesn’t necessarily work - not if what you are imitating is just different – not better.

Now that that is out of the way, let’s get to the point of the post.

- The Feature: Reopen Closed Tab

- The Problem

- The Release

- Demo

- Analysis of the Differences

- Copying Chrome

- Why Smaller Projects Copy Larger Ones

- Takeaways

On August 1, 2023, Mozilla released Firefox 116 and announced a change:

The keyboard shortcut to reopen closed tabs (command + shift + t) now reopens last closed tab or last closed window, in the order items were closed. If there aren’t any tabs or windows to reopen, this command restores the previous session. This change is in anticipation of upcoming changes to recently closed tabs.

If you have ever used Chrome (and have used this particular keyboard shortcut), you may recognize that the description of the change describes the way this feature works in Chrome.

Apparently, Mozilla has decided – after 19 years – that the Chrome behavior for the way this shortcut works is better, and has copied it. Chrome users rejoice.

Unfortunately for Firefox and Chrome users alike, the Chrome way isn’t necessarily better - and Firefox copied the Chrome behavior imperfectly – more on this later.

The Feature: Reopen Closed Tab

You’re two hours deep into a social media browsing session, and you’ve been opening and closing tabs left and right. Oops! You just closed a tab prematurely. How do you get the tab back?

Well, it is generally pretty easy - a quick shortcut that restores your last closed tab. If you’ve ever needed it, you know it can be a godsend.

The Problem

When Google introduced Chrome, they included a similar “reopen closed tab” feature (the menu item has the same label), but it worked differently from other browsers.

The biggest difference is that Chrome’s feature didn’t care about where the last closed tab was being restored from.

See, while Firefox had a “reopen closed tab” feature, it also had a “reopen closed window” feature.

In Firefox

- Control + Shift + T - Reopens tabs closed from the window that has focus

- Control + Shift + N - Reopens windows that are closed

In Chrome

- Control + Shift + T - Reopens closed tabs

- Control + Shift + N - Opens an “incogninto” window

The complaint I hear most from Chrome users over the years about this area of functionality is that “after I restart Firefox, I want to be able to just Control + Shift + T my way back into my previous session”, which seems to be something that people routinely do with Chrome.

I always point them to Firefox’s session restore feature, but invariably, the former Chrome user will say something like “why can’t it just be like Chrome?”

Well, some of the time (I would say a lot of the time), it is because the Firefox way is better, not just different.

Mozilla misses the mark when they replace better working functionality with more familiar facsimiles.

The Release

It’s release day as I write this. I had seen the coverage from a blog the day before and was expecting no major changes to my everyday experience, since I have a large session and I use the session restore feature in Firefox.

This morning, metasieben posted in a chat that:

the new restore tab/win functionality might still be a bit buggy. either that or i don’t understand how it should work. try tearing out a tab, then moving it back. why does undo tab-close reopen the window with the “moved” tab?

A couple of hours later, I had filed a bug.

Bugs happen. I think that the way the bug is triggered is enough off of the “happy path” that I can understand why it wasn’t seen in testing.

As I investigated further, however, I got a hint that perhaps this wasn’t as carefully planned as I would have hoped.

But first… a demo.

Demo

We’ve been talking about keyboard shortcuts this entire post and it is because most people who care about this feature enough to talk about it are the kind of people who use keyboard shortcuts – even you (especially you, you are reading this post!).

Now that we have established that you are a nerd, let’s talk about how a “normal” person uses this feature (if they are lucky).

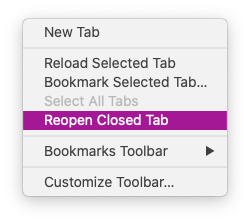

Context click in the tab strip of the browser you are using (don’t try this if you are using Lynx, Ladybird, Servo, or similar) - look there, it’s a menu item – Reopen Closed Tab.

If you aren’t using the keyboard shortcut, you are most likely using the contextual menu item.

Now, onto the video (it’s my first one on this blog!).

Chrome

It can be easy to miss what you are supposed to be looking at in any video, so here’s what to watch out for:

- I opened two windows in Chrome

- I had two tabs in each of the two windows

- I closed one tab in each of the two windows

- I context clicked in the tab strip of the window where I closed the next to the last tab

- I selected Reopen Closed Tab

- The tab that was reopened was in the other window, not the one where I had clicked

Firefox

I recorded a similar video for Firefox. As earlier, it can be easy to miss the key moments, so here’s what to watch out for:

- I opened two windows in Firefox

- I had two tabs in each of the two windows

- I closed one tab in each of the two windows

- I context clicked in the tab strip of the window where I closed the next to the last tab

- I selected Reopen Closed Tab

- The tab that was reopened was from the same window that I had clicked on, even though it wasn’t the last closed tab

Analysis of the Differences

You watched the videos. You can see that they are different. Which is better?

I think that the Firefox implementation is better, and that’s not just based on a gut feeling.

The Firefox feature works most coherently with the laws of locality:

If you’re ever wondering where you should put a control (meaning: a button, a dropdown, an icon, a search bar – whatever!), the answer is almost always: where it effects change.

It’s simple: the tab that gets reopened in Firefox is always going to be near where the user issued the command, because the tab is always going to be restored from the same window the user context clicked.

In Chrome, the resulting tab can appear on a different desktop or display - and while Chrome does a good of moving your focus to the reopened tab, it isn’t necessarily near where you clicked to reopen the closed tab.

Beyond that, I will often close tabs in quick succession, in different windows. If I want to reopen a tab from my “work” window instead of my “personal” window, why would I prefer it if Chrome reopened my “personal” tab instead? Chrome is less efficient!

It was while exploring this exact scenario where I discovered that the updated feature in Firefox… might be broken.

Copying Chrome

I linked to the Firefox release notes earlier, but in an open source project, if you want more information about a feature, you can generally look at the issue tracker to find out more.

Since I had reported a bug with this exact feature, this was really easy to find - see bug 1833416.

I won’t reproduce the entire bug here, but a straightforward reading of the bug shows that it was implemented incorrectly:

Ctrl/Cmd+Shift+T reopens things as the user closed them. In that way, it behaves like Undo (without the time bound nature).

So, if one tab was recently closed, Ctrl/Cmd+Shift+T reopens that.

Unfortunately, this isn’t actually how it works.

The copy above matches Chrome’s behavior - as designed, Firefox should match Chrome today. Chrome doesn’t care about which window the last closed tab was part of when it reopens a tab.

Firefox still does.

When you reopen a tab in Firefox 116, it always opens the last tab closed from the window that was in focus when you issued the command (either via the keyboard shortcut or the contextual menu item). Look at the videos on this page to see for yourself.

That is contrary to the designed behavior in the bug and the actual Chrome behavior.

To be totally clear and upfront with you, dear reader, I prefer it this way - the feature in Firefox 116 and prior. That’s why I haven’t opened a bug and wrote this post instead. But this isn’t what was designed, and it doesn’t seem to me that this is what Mozilla was thinking when they imagined this being shipped.

Why Smaller Projects Copy Larger Ones

Of course, in this and many other scenarios, Mozilla is caught in a bind. Is a feature better because the market leader (Chrome in this case) does it, or is it just better?

That’s a bit of a cop-out, though - and we know it. The people that Mozilla employs (and who are involved as contributors) are all smart, capable people who can at least attempt to try to figure out whether differences are merely bikeshedding or whether we need to apply real design thinking to decide how to proceed.

The reason that Mozilla is in a bind is because there are generally two ways that people respond to the question:

(Is a feature better because the market leader (Chrome in this case) does it, or is it just better?)

- Yes, it is better because that’s how Chrome does it (and I am used to it!)

- Of course it is better the way Chrome does it – that is why they are doing it that way

The reason that people seem to answer thusly seems to me to often be due to frustration - they’ve been told that Firefox is better and that they should use it. They have used other “different” browsers before - Edge, Opera – they were pretty much exactly like Chrome, except with a few more doodads here and there. Then they boot up Firefox - it’s very similar, but some of the similarity is skin deep. Core features work differently. Features that they rely on work differently. They may not even be present.

Why can’t it just be like Chrome?!?

At that moment, they may not really be interested in finding out whether the feature is actually implemented better in Firefox.

Mozilla sees that frustration. Maybe they see it as a “leaky bucket” where Chrome switchers are dripping out of the Firefox acquisition funnel. So they decide to plug it.

What’s the easiest way to plug it?

Do what people have been asking for ever since Chrome overtook you in marketshare - do what Chrome does.

So that’s what gets written up.

But it isn’t what gets built.

I’m not looking a gift horse in the mouth - I’m not questioning why the feature doesn’t match Chrome.

But who will care? The same people who Mozilla attempted to keep inside the acquisition funnel for Firefox!

So what have we accomplished here so far?

Right now, Firefox has a new feature that allows for a high degree of continuity for existing Firefox users. This likely explains why more bugs weren’t caught and there wasn’t more user outcry. This release also adds a new feature - it gives people who aren’t opted into session restore a faster way to restore their tabs and windows after they restart their Firefox session.

In terms of delivering features to people who now like Firefox and didn’t want to opt into session restore automatically (but want the option to do it faster manually), I think it’s fine. It’s weird that it recharacterizes an existing keyboard shortcut, but it’s not like it was going to do anything else otherwise – it is a brand new session. I say, let ‘em have it.

What if you are a die-hard Chrome user, though? This won’t do.

Clearly, since Chrome does it differently, it must be better, and what Firefox continues to do is worse, so why did Mozilla just keep iterating on the same broken design?

Mozilla (Probably) Wanted it to be Like Chrome

It looks to me like Mozilla wanted this feature to act like it does in Chrome.

Why?

The simplest reason is that that is the way it is written.

Beyond that, I assume Mozilla is routinely comparing product functionality to its competitors for competitive analysis. Being more like Chrome in areas where differentiation isn’t valued (and marketable as such) is exactly the reason that Microsoft moved to Chromium as the core of its browser - among other ways to reduce costs, it reduces switching costs for users – even if the implementation is worse!

So in that regard, it probably seemed like a safe, easy choice. Sure, you might annoy some of your own users, but there are so many potential new users used to doing it the way you’re going to do it. That’s going to be awesome.

Except that’s not what got released. How does this work?

How does a feature get released that doesn’t do what it says it does - either in the original bug ticket or in the release notes? How is it supposed to do anything but annoy potential Chrome switchers who try out the browser based on what the release notes (and media) say, and who discover that it does the same “broken” stuff Firefox has always done?

How does it not make the “leaky bucket” problem worse?

How Firefox Really Loses

Firefox loses when it doesn’t do the work, when it copies Chrome blindly.

As I wrote in bug 1693028 back when Mozilla unsupported the toolbar compact density option in Firefox:

The story also says that “and we assume gets low engagement” which sounds to me like we don’t actually have hard data around this, and are instead guessing based on what feels like low discoverability (although I would argue that the option is exactly where it ought to be).

I suspected then the feature was cut because they hadn’t considered it. I don’t know if that is the case, but as I said then, the language used seems to indicate that.

The situation with “undo closed tab” is different. Here, Mozilla:

- likely decided to copy Chrome

- wrote it up as such

- didn’t implement it that way

- announced it as if they had done it that way

So what’s happening here? Like Proton, this feature seems so rushed that it doesn’t even meet the clear-as-day acceptance criteria. This also means that Mozilla can’t even be bothered to ensure that the feature as released is what they meant to release.

I think it is a false economy to want to rush out functionality that isn’t well designed. Just releasing something new isn’t a success.

I don’t intend to judge anyone. As a tech worker myself, I know that these jobs can be hard, stressful, thankless, and confusing.

I wrote this post because it isn’t enough to just copy the market leader when you already have a dedicated and loyal userbase.

Firefox isn’t some brand new product, the people using it like it – there is virtually no way for its users to not like it, with the way that bad teams ignore web standards.

When a company intends to conquest users from another, larger group of people, it is clearly tempting to want to simply jettison your existing userbase as fuddy duddies who are just so loyal to this legacy product that you can push whatever change you want to them.

If you are truly malevelont, you can do what Reddit has done and kill off your competition so that you can abuse your userbase with impunity.

Maybe that is fine when you really do have that kind of userbase.

I don’t think that’s the Firefox userbase.

For many of the areas where Firefox is different than Chrome, Firefox is better. I think that there is a very simple reason for that. Mozilla over the years had thought deeply about how features ought to work, and built very high quality experiences into their products.

Even as its crufty internals helped betray Firefox’s marketshare due to stability and performance issues (made worse due to the desire to support legacy extensions), Firefox continued to have pockets of very well thought through user experiences.

Of course, if you were a Chrome user, you wouldn’t know that – especially if you believe that the Chrome way must be superior because that is the way it is in Chrome.

I’m not conviced that might makes right, and I believe that competition makes ecosystems better. It is understandable that a Chrome user might be unfamiliar with Firefox and may need some hand-holding if they are attempting to make a change.

It is entirely possible for competitors to have better designed experiences - but I don’t think it makes sense to assume that because a competitor is more successful in market, that the experience must be better.

People understand that in other spaces. Is McDonald’s better than the farm-to-table restaurant in your downtown? It must be, McDonald’s market capitalization dwarfs that of the smaller resturant. Clearly that means that the food, the ambiance, the service… are better.

Clearly, we can’t assume that because someone has a richer or larger team, that what they produce must be better, and we shouldn’t be convinced otherwise.

Takeaways

There a few takeaways for me.

More Market Success Isn’t an Excuse to Stop Thinking

It is easy to fall prey to hype, mania, or trends – especially when it seems like people are enjoying great success – and then immediately try to cargo cult their behaviors.

This is very clearly a mistake, but if you don’t see why, think about blockchain, NFTs, and even cryptocurrencies. What happened there? A lot of people lost a lot of money, but before the bottom fell out, seemingly everyone was into it – even the rich and famous.

It seems obvious to me that instead of adopting behaviors unthinkingly, people ought to think about how they think those behaviors will result in success.

It is Okay to ask People to Explain Themselves

When considering whether something makes sense, you don’t have to guess at what people are thinking. Often, you can ask. You can look for evidence. You can read documentation.

If something seems wrong, you ought to feel empowered to say something. You might be wrong, but you don’t have to automatically assume others are right.

Often, others will have done the work, and you may feel chastened. Don’t. You learned something new, just as your interlocutor may have. Be intellectually curious and open to the possibility that you might learn something.

Your Biggest Competition is Your Last Version

No, seriously. Most of the bugs I file in any open source project are regressions. Even worse than broken new features, the worst bugs most people encounter are the ones that break things that used to work.

That was true in my experiences in tech support as well.

It is easy to understand why. People are used to existing functionality. They have habituated themselves to it. They may even rely on it. For new functionality, they may not have adopted it yet, they may not be interested, or the functionality may not be as integral to their workflow, freeing them from (as many) impacts from negative repurcussions.

So when projects introduce new functionality that “breaks” existing functionality, it needs to be considered much more carefully within that context – is the new functionality better enough that it will satisfy the people using your existing project?

Or is it possible that your new feature is worse enough that they would rather use your last version?

If You Want to Make a Change, You Have to Want to Make a Change

I often see posts about requests from Chrome switchers to Firefox that have made almost no effort to learn about how to accomplish their use cases in Firefox.

I completely understand that these are the people that Mozilla is likely targeting when making these changes.

Is that what you are looking for, though? Ask yourself - when I want to use an alternative product, do I want it exactly the same as what I am used to – even if it is worse than the experience that I would have had if I had learned something new?

If that is the way that the majority of people think, are we doomed to use the worst possible products pushed by companies that can afford to simply get people used to inferior products?

If you want something better, it is probably worth putting in the time to learn it. If you don’t think it is better, ask people to explain themselves - ideally by reading documentation, forum posts, or asking nicely.

Quality Matters

Quality matters. The work matters. Firefox recently overtook Chrome in the Speedometer benchmark. That didn’t happen by accident. It is the result of years of hard work, both in “infrastructure” projects like Firefox Profiler and Rust, but also in the hard work of tracking down and fixing the dependent bugs that led to the superior result versus a much richer company.

You don’t cargo cult your approach to quality if you actually want it to work.

Just copying your competitors doesn’t guarantee quality. Without understanding of why it is that something is better, you can only assume that it is different.

There are no Easy Answers

This may be the toughest pill to swallow.

Any change you make – even good changes – are going to be disliked by some.

The risk of a change dissatisfying more people goes up as it is used by more people, and in mature products, many changes are going to end up getting a lot of scrutiny - because people are used to existing functionality.

That means that there are no easy answers - when evaluating changes in mature products with many users, you need to do the work to be able to effectively respond to your existing userbase when they ask why some new functionality is better than what existed previously.

The silver lining here is that doing the work means that you have a lot more confidence in making those changes. You have evidence on your side, not just cargo cult thinking.

Ultimately, Firefox loses when it loses the good things that make Firefox better than the competition. If Chrome (or any other browser) is doing something better than Chrome, by all means, copy it – or do it better. If you don’t know it is better, there is no “easy” choice to make (the risk may be minimal if the feature is not well liked or used by many people).

Is that what Chome users are thinking about when they demand exact feature copies? Is that what Mozilla is thinking about if they think copying features is easy?

Of course not. They are taking shortcuts. We all are.

It is easy to miss things if you aren’t looking for issues. There are no easy answers.

If you liked this post, please consider supporting what I do. Feel free to give me feedback on this post on Kbin. You can also message me on Mastodon.